Nordlys Film Festival a success

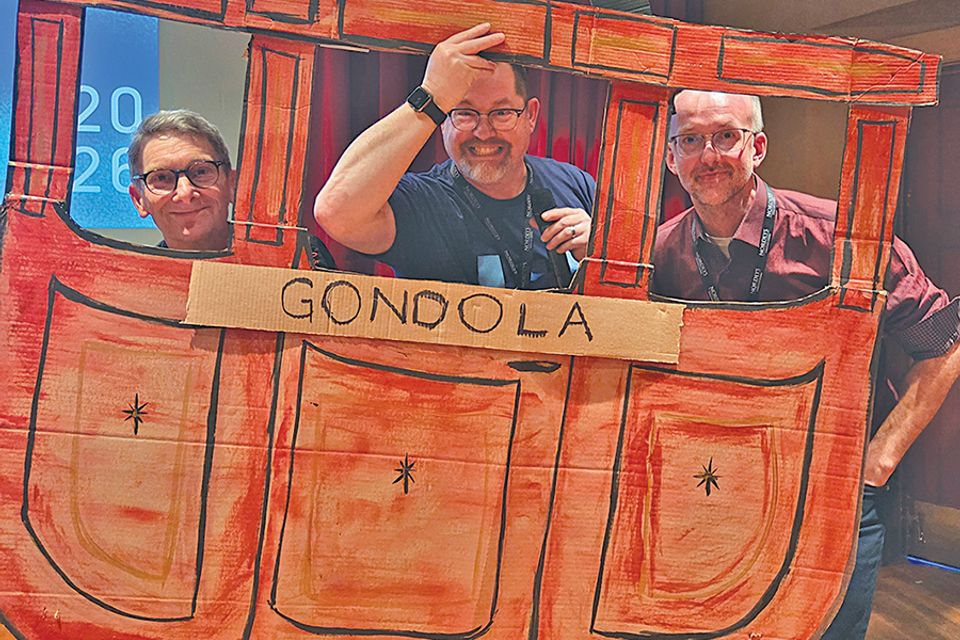

The 2026 Nordlys Film and Arts Festival was once again a success. From left, local artist Jim Malmberg, board member Dwayne Wohlgemuth and emcee Steve Hansen take a ride on the gondola as Dwayne introduced the film Gondola to the audience.

By Nadine Leming

With another Nordlys Film and Arts Festival in the books, the board of directors alongside committee members can be proud of a fantastic weekend. The event was host to an eclectic lineup of films and included the first ever live play.

The weekend opened with a cocktail hour with hors d’oeuvres supplied by local vendors prior to the opening ceremony. People came dressed for the occasion, many in suit and tie, beautiful dresses and even one guest in a fascinator for Camrose’s premier event of the year.

Mardell Olson, president of the Nordlys Film and Arts Festival, welcomed everyone to the 17th annual festival. She took a moment to thank all of the regular and first time attendees. During her opening remarks, Mardell said, “Nordlys is a volunteer-run event and we want to extend a huge thank you to our hard-working board and committee members.”

She made a special point of thanking everyone from ushers and concession volunteers to people that delivered posters and those that helped with coat check. She added, “The Bailey Theater takes such good care of us, from selling tickets to providing us with a stellar tech team, we are so thankful to them. We couldn’t do what we do without our generous community sponsors.”

The first show for audiences to enjoy was the stage play, Evie and Alfie: A Very British Love Story starring Alex Dallas and Jimmy Hogg. These talented award-winning actors portrayed a humorous look at the ups and downs of life, marriage, raising a child, a potential affair and a health scare in a way that was hilarious and relatable to everyone. At one point, Alfie compared himself to Gandhi. The show received a standing ovation from the enthusiastic crowd.

In the question and answer session after the show, Alex commented, “I think since ancient Greek times, people have worried that theater will die. I don’t think it ever will, it’s the only thing that can’t really be AI.” She went on to explain that during live theatre the audience is sharing the human experience and as long as there are people on this planet, we will tell each other stories.

The weekend included a variety of films from around the globe such as A Poet, The Ballad of Wallis Island and Gondola, all offering something unique and different to festival attendees.

Master of Ceremonies Steven Hansen kept audiences on their toes with his quick wit and sense of humour throughout the weekend, adding his wonderful take on things as the one-and-only emcee the festival has ever known could.

Folktales and Siksikakowan: The Blackfoot Man were documentaries filled with emotion and authenticity, both telling stories of the human experience, of personal growth while leading to personal triumphs of each of the people featured.

These stirring and emotionally impacting stories allowed many the opportunity for personal introspection and reflection.

Another unique feature of this year’s event was the display of art by artist Dale Moostoos. He created a special temporary Nordlys tattoo for anyone interested in getting one.

Hailing from Sturgeon Lake Cree Nation, this talented artist’s work includes traditional Indigenous beading, and moose hair tufting. He has a strong background in painting, drawing and sculpting.

He grew up hunting and fishing, feeling connected to the land and it is that passion he is trying to pass on to his children. His work is truly remarkable.

In between films at Café Voltaire, the community was treated to the musical stylings of a wide range of local talent that included Tindall Hartman and Olson, Jim and Penny Malmberg, Stephen Olson and more.

The weekend concluded after the last film of the weekend with the announcement of the Pretty Hill Award which was awarded to the film DJ Ahmet, which was a bittersweet story of a 15-year-old boy from a remote Yuruk village in North Macedonia.

It was then time for the after party with music provided by Gus Gustopherson, who last performed at the film festival 20 years ago when it was still the Pretty Hill Film Festival.

To no one’s surprise, this event sells out every year. For anyone who was unable to attend, but would like to see films from this year as well as past years, they are encouraged to visit the Camrose Public Library to borrow them.

By Nadine Leming

With another Nordlys Film and Arts Festival in the books, the board of directors alongside committee members can be proud of a fantastic weekend. The event was host to an eclectic lineup of films and included the first ever live play.

The weekend opened with a cocktail hour with hors d’oeuvres supplied by local vendors prior to the opening ceremony. People came dressed for the occasion, many in suit and tie, beautiful dresses and even one guest in a fascinator for Camrose’s premier event of the year.

Mardell Olson, president of the Nordlys Film and Arts Festival, welcomed everyone to the 17th annual festival. She took a moment to thank all of the regular and first time attendees. During her opening remarks, Mardell said, “Nordlys is a volunteer-run event and we want to extend a huge thank you to our hard-working board and committee members.”

She made a special point of thanking everyone from ushers and concession volunteers to people that delivered posters and those that helped with coat check. She added, “The Bailey Theater takes such good care of us, from selling tickets to providing us with a stellar tech team, we are so thankful to them. We couldn’t do what we do without our generous community sponsors.”

The first show for audiences to enjoy was the stage play, Evie and Alfie: A Very British Love Story starring Alex Dallas and Jimmy Hogg. These talented award-winning actors portrayed a humorous look at the ups and downs of life, marriage, raising a child, a potential affair and a health scare in a way that was hilarious and relatable to everyone. At one point, Alfie compared himself to Gandhi. The show received a standing ovation from the enthusiastic crowd.

In the question and answer session after the show, Alex commented, “I think since ancient Greek times, people have worried that theater will die. I don’t think it ever will, it’s the only thing that can’t really be AI.” She went on to explain that during live theatre the audience is sharing the human experience and as long as there are people on this planet, we will tell each other stories.

The weekend included a variety of films from around the globe such as A Poet, The Ballad of Wallis Island and Gondola, all offering something unique and different to festival attendees.

Master of Ceremonies Steven Hansen kept audiences on their toes with his quick wit and sense of humour throughout the weekend, adding his wonderful take on things as the one-and-only emcee the festival has ever known could.

Folktales and Siksikakowan: The Blackfoot Man were documentaries filled with emotion and authenticity, both telling stories of the human experience, of personal growth while leading to personal triumphs of each of the people featured.

These stirring and emotionally impacting stories allowed many the opportunity for personal introspection and reflection.

Another unique feature of this year’s event was the display of art by artist Dale Moostoos. He created a special temporary Nordlys tattoo for anyone interested in getting one.

Hailing from Sturgeon Lake Cree Nation, this talented artist’s work includes traditional Indigenous beading, and moose hair tufting. He has a strong background in painting, drawing and sculpting.

He grew up hunting and fishing, feeling connected to the land and it is that passion he is trying to pass on to his children. His work is truly remarkable.

In between films at Café Voltaire, the community was treated to the musical stylings of a wide range of local talent that included Tindall Hartman and Olson, Jim and Penny Malmberg, Stephen Olson and more.

The weekend concluded after the last film of the weekend with the announcement of the Pretty Hill Award which was awarded to the film DJ Ahmet, which was a bittersweet story of a 15-year-old boy from a remote Yuruk village in North Macedonia.

It was then time for the after party with music provided by Gus Gustopherson, who last performed at the film festival 20 years ago when it was still the Pretty Hill Film Festival.

To no one’s surprise, this event sells out every year. For anyone who was unable to attend, but would like to see films from this year as well as past years, they are encouraged to visit the Camrose Public Library to borrow them.